The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek

A Tragic Clash Between White and Native America

About the Book

Published 2011 by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

An Editor’s Choice Selection of the New York Times Book Review

The nearly 400-year confrontation between the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere and the white settlers from Europe was marked from first to last by the newcomers’ conviction that they were entitled – by cultural superiority, moral enlightenment, and God’s grace – to displace the primitive inhabitants and make the land their own.

Among the last places in North America where this stark racial collision played itself out was the bountiful Puget Sound region in what was then known as the Washington Territory in the northwestern corner of the United States. There, thanks to moderate climate, sheltering mountain ranges, lush forests, crystal-pure waterways teeming with wildlife, and the absence of predatory neighbors, the local tribes had prospered in their remote paradise for some 10,000 years.

All that suddenly ended in the middle of the nineteenth century when a proud, retired young U.S. Army major, an engineer with high political ambitions, was appointed the first governor of newly acquired, 100,000-square-mile Washington Territory. Isaac Ingalls Stevens’s primary task was to persuade the natives that their only hope for survival was to sign treaties handing over their ancestral lands to the American government in exchange for protection from oncoming whites eager to turn the wilderness into crop- land. But one tribal chief at Puget Sound, Leschi of the Nisqually nation, insisted that his people be dealt with fairly and not coerced into surrendering virtually their entire sacred homeland without just compensation. The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek is the emblematic story of this confrontation between the headstrong American governor and the defiant leader of the Nisquallies and their brethren who resisted him and, in doing so, stirred up the gross abuse of power and the licensing of injustice on our last frontier.

land. But one tribal chief at Puget Sound, Leschi of the Nisqually nation, insisted that his people be dealt with fairly and not coerced into surrendering virtually their entire sacred homeland without just compensation. The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek is the emblematic story of this confrontation between the headstrong American governor and the defiant leader of the Nisquallies and their brethren who resisted him and, in doing so, stirred up the gross abuse of power and the licensing of injustice on our last frontier.

Here is Richard Kluger’s poignant rendering of the tragic relationship between the red and white races, told in graphic detail. Our social literature abounds with accounts of how racist degradation was visited on the far more numerous black and Hispanic Americans. Yet the nation’s self-righteous, methodical dispossession of the Indians has been largely dismissed by whites as the sad but inevitable price of social and technological progress. Through the experience of a single tribe, The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek seeks to clarify the historical record. It also tells, in a hopeful epilogue, the latest chapter of the Nisqually tribe’s struggle to endure amid the mounting pressures of twenty-first-century modernity.

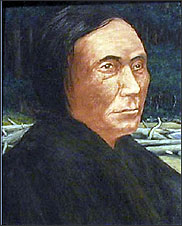

Chief Leschi

A Q&A with the author

Question: How did you first hear about the Nisqually nation and what drew you to their story?

Answer: It was pure chance that I came upon this little-known episode in American history. And from the moment I learned of it, I thought it spoke volumes about the nature of the tragic encounter between the red and white races on our continent

Setting out to research a historical novel I wanted to write about a circuit-riding judge trying to bring law and order to the western U.S. during its roistering frontier days, I telephoned the Washington State Law Library in Olympia to inquire if records still existed of court cases heard by judges during the thirty-nine years Washington was a federal territory before entering the Union as a state in 1889. To my delight, the librarian reported that a great many documents survived casting light on the rough-and-tumble sort of justice dispensed back then while America was sprouting into a continental nation. Then, out of the blue, the librarian suggested that I might want to look into the third case ever heard by the Washington Territorial Supreme Court. “Why – what was special about it?” I asked.

“Well,” she explained, “it was the first appeal of a capital case ever heard up here – a plea to reverse the murder conviction of a Native American tribal chief for killing a militiaman. What’s so remarkable is that in 2004, a special tribunal of judges, presided over by the chief justice of our Washington State Supreme Court, voted unanimously, in effect, to reverse the territorial court’s 1857 decision and unofficially exonerate the tribal chief – Leschi of the Nisqually tribe.”

“Wasn’t that a little late in the game?” I asked, surprised by her revelation.

Better late than never, the astute law librarian said, suggesting that the case said a great deal about just how the northwest corner of the U.S. was settled. “You might want to look into it.”

And so I did – and what I found, I believe, is a microcosm of the much larger, very painful story of racial conflict between the native people and the newcomers determined to replace them.

Q: Can you tell us a little about the Nisqually tribe and what the region they lived in was like at the time you write about?

A: There were probably never more than 1,000 or so members of the Nisqually tribe, who lived peaceably – and well – for many millennia along the banks of a pristine river that flowed down from the glaciers on majestic Mount Rainier and ran 80 miles into Puget Sound, a secluded arm of the Pacific Ocean that reached about 100 miles inland. This remote location served the tribe perfectly – the place was a virtual paradise, with temperate weather, lush grasslands, towering forests, and a crisscross of waterways, all teeming with fish and game, and long protected from white settlers and other potential enemies by the soaring Cascade Range. The great red cedars provided the Nisquallies with all their housing, transportation (dugout canoes), and clothing needs, and salmon, shellfish, deer, and wild berries were everywhere. Thus blessed, the Nisquallies and other tribes in that region – among the very last Indians the white settlers discovered – were unprepared for the sudden incursion of a technologically advanced civilization, which was not interested in sharing the land with unsuspecting natives like the Nisquallies, who had initially greeted them with kindness and assistance.

Q: So much has been written about the war waged on Native Americans in this country. What made you feel there was something new to be said about this story?

A: I’d say that while most Americans know something about this perhaps saddest chapter in our national history, they know very little about the particulars, about why and how it happened. For example, almost everyone who has ever taken a high school course in U.S. history knows that despite the assertion in the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal, the Constitution egregiously denied equal rights to blacks. But few Americans are aware that among the first acts by the U.S. Congress was a pledge that no lands would be taken away from Indian tribes without their consent – a promise never even remotely honored.

White Americans naturally do not like to be reminded of their long history of mistreatment of people of color. And the truth is, for the past half-century they have been afflicted by something resembling a national guilty conscience over this thick catalogue of racist abuses and have been acting in ways to correct this massive incivility. The recent election of our first black President and his appointment of the first Latino to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court are emblematic of this evolving change of heart – a long overdue gesture of respect by whites to their fellow Americans. Asian Americans, too, are increasingly being recognized for their achievements and contributions to our society.

Far less visible amid this surge of multiracial validation in the U.S. – and rarely granted more than lip-service acknowledgment of their long victimization – has been the oldest and now the nation’s smallest racial minority: those of native blood, the remnant of a so-called red race that migrated to this hemisphere from Asia and Oceana starting some 10,000 years ago yet accorded the dignity of full citizenship only in 1924. Their antiquity has hardly served to ensure their survival or enhance their status in the American social hierarchy.

Native Americans have been permitted to choose between slow extinction on bleak reservations or self-exile from Indian Country to uncongenial urban surroundings, where acculturation has often proven traumatic. By the beginning of this century, more of the estimated 2.75 million people (under 1 percent of the national total) identifying themselves as Native Americans – which generally requires at least one-quarter Indian blood – lived in cities and towns, not on or close to reservations. This drastic decline of the natives as a distinctive ethnic classification has become a sad, dispiriting chapter in our national narrative. Those remaining as members of the roughly 500 federally recognized tribes, communities, and bands have for several generations now been more pitied than scorned. But most of the rest of us still believe – if pressed on the subject – that the marginalization of the Indians and the methodical removal of their once vast holdings were the regrettable price that had to be paid if human evolution was to progress on this continent. At least we now rarely vilify tribal people or make movies depicting them as good for little more than target practice by the U.S. cavalry.

Q: So we are making progress in dealing with the Native Americans?

A: A little. And at least we now have an American Indian museum on the Capitol Mall. But far from viewing them as a genuine national treasure with a culture worth preserving, Americans too commonly tend to think of Indians as an exotic memento mori, anomalous curios, drugged up and shiftless, broken and unfixable. Only a recent and controversial exercise of massive affirmative action by the U.S. government, in the form of laws licensing gaming casinos in Indian Country, has begun to alleviate some of Native America’s extreme economic distress.

Q: What’s been behind this generally dismissive attitude?

A: The failure by nontribal people to appreciate the nature of the natives’ grievances and how to address them. The Indians do not clamor for the nation’s ear, demanding economic parity and the profits of free enterprise, because they are not, for the most part, animated by the American Dream of maximum personal self-aggrandizement. They are not worshippers at the shrine of rugged individualism. They are, through cultural conditioning that has endured for millennia, a communal and interdependent people; they need one another. And they are, I would venture, a more spiritual people than most who dwell in America, however godly the rest of us may profess ourselves, and they are, for the most part, less materialistic and mercenary. Liberty and prosperity for all, in their case, mean freedom from harassment by outsiders and a shared commonwealth of well-being, not greater opportunity for the most aggressive among them to thrive while the rest are left to founder. The tribes are collectives, whose pursuit of happiness is a shared venture – a practice decidedly against the American grain.

In recent years, under the spell of an insistent, presumably soothing political correctness, we have shied from using the word “Indian” – a misnomer from the beginning – and taken to calling tribal people Native Americans. But “American” is, of course, a European-derived word and concept; the natives here were not Americans but pre-Americans. Their ancestors preceded the white settlers by thousands of years, and they do not ask for or need to be granted social certification by races who have avidly muscled them out of the way.

Q: Did you write this book because you wanted to cast light on a largely unknown chapter in our history or because you hope to change current attitudes? What do you hope readers will take away from your book?

A: The Bitter Waters of Medicine Creek does not attempt an encyclopedic survey of the interaction between the red and white races on these shores – so calamitous to the former, so ignoble of the latter. It is not meant to be a compendium but an illustration. In focusing on the experience of a single small tribe, the book aspires to make more accessible and comprehensible a monumental tragedy; the narrower the scope of the narrative, the keener our perception may become of the unfolding human drama, personified by the clash between the two leading figures in the story, Washington’s territorial governo Isaac Stevens and Nisqually chief Leschi.

Q: What was the outcome?

A: The climax of the story is the 1856-7 murder trial and the appeal of its outcome in Washington Territory v. Leschi, an Indian, an all but forgotten court case, but one that was revisited in 2004 by Washington state judges and lawmakers. The very obscurity of these circumstances, I feel, invites cool reflection on the issues at their core instead of indifference to a familiar and depressing eyesore on our cultural landscape. Call it a fresh reckoning.

When I logged on line at the beginning of my research and read the appeal court’s 1857 ruling, its first few sentences betrayed a transparently racist tone suggesting that something less than a disinterested quality of justice was about to be rendered. Events over the three years preceding the court’s decision, my subsequent investigation disclosed, were shaped by a similarly phobic disposition among Washington Territory’s citizenry at large. Why this should have been so is a question, I believe, worthy of consideration even at this seemingly late date. We are still a young nation, and for all our prodigious feats to date, our future prospects are likely to turn on our ability to learn from how we have erred as well as succeeded.

Q: What became of the Nisqually tribe – did it survive into modern times?

A: Very much so – but it hasn’t been easy. In 1917, the U.S. Department of War forcibly bought up two-thirds of the tribe’s already small reservation to form part of Fort Lewis, a new military base, reducing the natives’ homeland to a postage-stamp of two square miles (1,280 acres). Many of the tribal members drifted away, and only a few dozen families remained. In 1960 there was still no running water or electricity at the reservation, and almost no government or educational services available.

But starting in the 1970s, federal funds began to flow to the reservation and a tribal headquarters building was constructed. Things really started to change, though, in the late 1980s when Congress allowed gambling casinos to be built on tribal lands under federal monitoring – a form of affirmative action. The Nisquallies started with a bingo hall in the 1990s and then converted it into a casino with slot machines, a big tourist attraction, and did well enough to build a Vegas-style facility in 2004 that they named Red Wind Casino with more than 1,000 slot machines and most of the other games of chance that lure customers through the doors even in a relatively rural setting. In 2009, Red Wind grossed nearly $100 million, of which $35 million was profit for the 675 or so Nisquallies who make up the tribe’s present population. That’s more than $50,000 per capita, and the money goes not only to subsidize individual tribe members’ living costs but for increased social and health services, recreation facilities, new housing, and other tribally owned enterprises. A new generation, overcoming the plagues of alcohol, drug addiction, idleness, and despair, has come to the fore and is educating itself as no earlier generation has done since the coming of the white man to their domain. Now there’s hope that the tribe can endure and even prosper as a sustainable subculture within the American mainstream.

©2017 Richard Kluger